City walls in ancient China were never merely about defense—they were statements of power, order, and harmony with the cosmos. For an architect, Chinese city walls offer an extraordinary lens into the country’s long-standing tradition of urban planning, construction techniques, and philosophical underpinnings. From massive imperial capitals to compact county seats, these ancient enclosures evoke the genius and spirit of Chinese civilization. This article explores the architecture of Chinese city walls, their symbolic meaning, and their relevance to concepts like fengshui and spatial hierarchy, offering a journey into the built legacy of China’s walled cities.

The Tradition of Enclosure in Chinese Architecture

Walls as Manifestations of Order

Enclosure is a fundamental principle in traditional Chinese architecture. From courtyard houses to imperial palaces and Buddhist temples, physical boundaries are used to define social status, function, and orientation. Chinese city walls were the ultimate expression of this philosophy on an urban scale. They created a clearly defined space, separating the civilized interior from the unpredictable wilderness beyond.

The concept of “fang” (坊), or ward, within Chinese urban planning reinforces this enclosure mindset. Walled grids of residential neighborhoods allowed for social control and centralized governance. In a sense, Chinese city walls were not just protective barriers but tools of administrative logic.

Fengshui and Cosmological Alignments

Chinese city walls were often designed following fengshui principles and geomantic orientation. Cities such as Xi’an, the capital of the Tang dynasty, were laid out with symmetrical precision, aligned with cardinal directions. The square or rectangular shape of many city walls symbolized Earth (in Chinese cosmology), while the placement of gates allowed energy (qi) to circulate in harmony.

Iconic Chinese City Walls Worth Exploring

Xi’an – A Living Example of Ming Military Precision

The city wall of Xi’an is arguably the best-preserved among ancient Chinese city walls. Rebuilt during the Ming dynasty in the 14th century, the wall stands as a monumental rectangle stretching over 13 kilometers. Its massive brick-faced structure, complete with moats, watchtowers, and parapets, demonstrates the standardization of military architecture during the Ming period.

The Xi’an wall’s preservation allows modern architects to study traditional defense systems, gate towers, and crenellation layouts in real scale. It offers insights into modular construction using tamped earth cores and brick exteriors—a hallmark of late imperial wall building.

Nanjing – A Blend of Topography and Grandeur

Another remarkable example is the city wall of Nanjing, constructed during the early Ming dynasty under Emperor Zhu Yuanzhang. Unlike the geometrically rigid Xi’an wall, Nanjing’s city wall flows with the terrain. Stretching over 35 kilometers in its original form, it integrated rivers and mountains into its design, showcasing the adaptability of Chinese engineers.

The bricks used in Nanjing’s wall bear the names of officials and artisans, providing rare documentation of ancient labor systems. This wall, more than just a fortification, exemplifies a large-scale public work blending artistry, politics, and practicality.

Pingyao – A Snapshot of a Walled Merchant Town

Unlike imperial cities, Pingyao in Shanxi province reflects a different scale and function. Its city wall, dating to the 14th century, encloses a town of about 2 square kilometers and maintains its original layout, gates, and towers.

Pingyao’s wall demonstrates how Chinese city walls were not solely military but also civic structures that supported economic life. For centuries, the wall protected banks, shops, and homes within, reinforcing the link between security and commerce.

The Great Wall and the Expansion of the City Wall Concept

Beyond Urban Boundaries

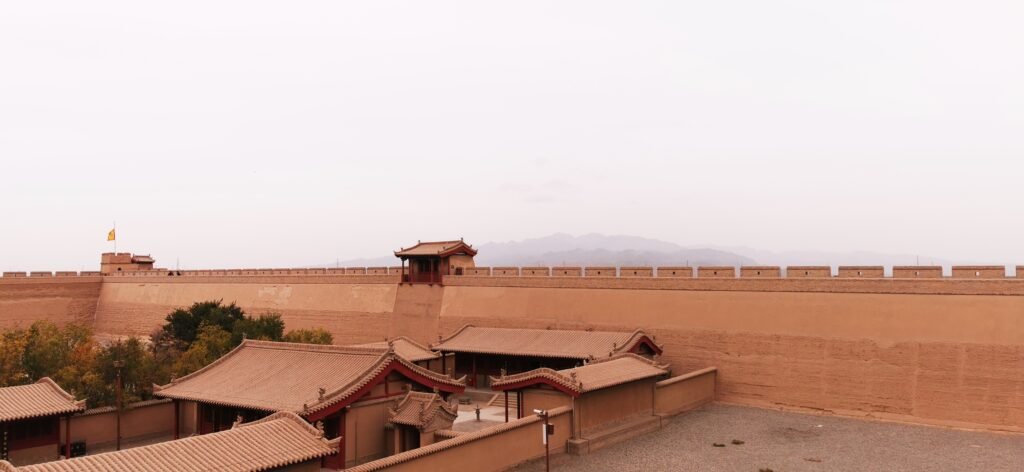

No discussion of Chinese city walls is complete without referencing the Great Wall, perhaps the most recognized symbol of China worldwide. While not a city wall per se, the Great Wall represents the evolution of wall-building into a national defense system. Originally a series of regional fortifications, it was consolidated during the Qin and Ming dynasties into a vast frontier wall.

Architecturally, the Great Wall shares many construction methods with city walls, including rammed earth cores, brick facing, and watchtowers. Its sheer scale, however, transforms the idea of enclosure from urban to imperial—a line encircling not a city but an entire civilization.

Defensive Logic and Symbolic Meaning

The Great Wall functioned both practically and ideologically. It kept nomadic tribes at bay while asserting a clear border between Han Chinese territory and the steppe cultures. For architects, this transition from city walls to frontier walls marks a fascinating shift in scale, ambition, and symbolism.

What City Walls Reveal About Ancient Chinese Society

Chinese city walls were physical maps of a society that valued hierarchy, harmony, and control. Their construction often reflected the administrative order: the capital wall emphasized imperial authority, provincial walls signaled regional power, and county walls ensured local governance.

Inside the walls, the city was often arranged along orthogonal axes. Government buildings sat at the northern end, mirroring palace arrangements in Chinese traditional architecture. Gates to the south welcomed guests and traders, symbolizing openness within an enclosed, ordered cosmos.

Preservation and Legacy in Modern China

Today, many Chinese city walls have disappeared under the pressure of modernization. Yet cities like Datong, Luoyang, and Jingzhou are restoring or preserving parts of their walls as symbols of cultural identity. These restorations are not just about heritage—they also inform contemporary architects interested in integrating tradition with modernity.

City walls influence modern urban planning in China as planners seek to balance density with historical preservation. The idea of enclosure is still relevant—seen in gated communities, park perimeters, and even courtyard-style architecture.

Conclusion: Why Chinese City Walls Still Inspire

For architects, Chinese city walls are more than relics—they are masterclasses in spatial logic, construction ingenuity, and cultural symbolism. Whether it’s the symmetrical fortresses of the Ming dynasty or the serpentine strength of the Great Wall, each wall tells a story about how the Chinese saw their cities, their society, and the world.

By studying these remarkable structures—from the walled city of Xi’an to the Great Wall itself—we understand not just how ancient China defended its people, but how it defined its civilization. These ancient enclosures continue to inspire architects, historians, and anyone passionate about the built environment.