Le Corbusier’s utopian city plan after the World War was not implemented in Europe but came true in Chinese cities by coincidence.

As we stroll through modern cities, gazing along wide, straight roads built for cars, we see rows of diverse buildings lining the streets. Most of these structures are rectangular, towering toward the sky. Cars move in orderly streams along the roads, office workers go about their duties in high-rises, and families in residential buildings prepare their evening meals. This is a typical urban scene, so commonplace that we often overlook the fact that this way of life has only existed for a few decades.

Before the end of World War II, the vast majority of people around the world lived in small houses—one or two stories tall, rarely exceeding five or six floors. These buildings were typically constructed from stone or brick, materials that lacked the structural stability needed for tall construction. Buildings made of wood were vulnerable to insect infestations, dampness, and the constant threat of fire. Streets were much narrower than today’s because they were designed for pedestrians rather than automobiles.

Le Corbusier: The Visionary Behind Modern Urban Growth

The transformation of cities from low-rise settlements to towering metropolises was driven not only by advances in reinforced concrete technology and structural engineering but also by the visionary insights of one architect: Le Corbusier.

Le Corbusier was a pioneer of the modernist architectural movement, working primarily from the 1920s to the post-war decades. Living through one of the most turbulent periods in human history, his work and ideas were clearly divided into two phases: before and after World War II.

Le Corbusier’s Early Explorations

Before the war, Le Corbusier focused on architectural design within the context of the Industrial Revolution. He foresaw the advent of the reinforced concrete era and actively explored its potential, both in structural innovation and aesthetic expression.

Two of his most iconic works from this period are the Villa Savoye and the Chapel of Notre Dame du Haut in Ronchamp.

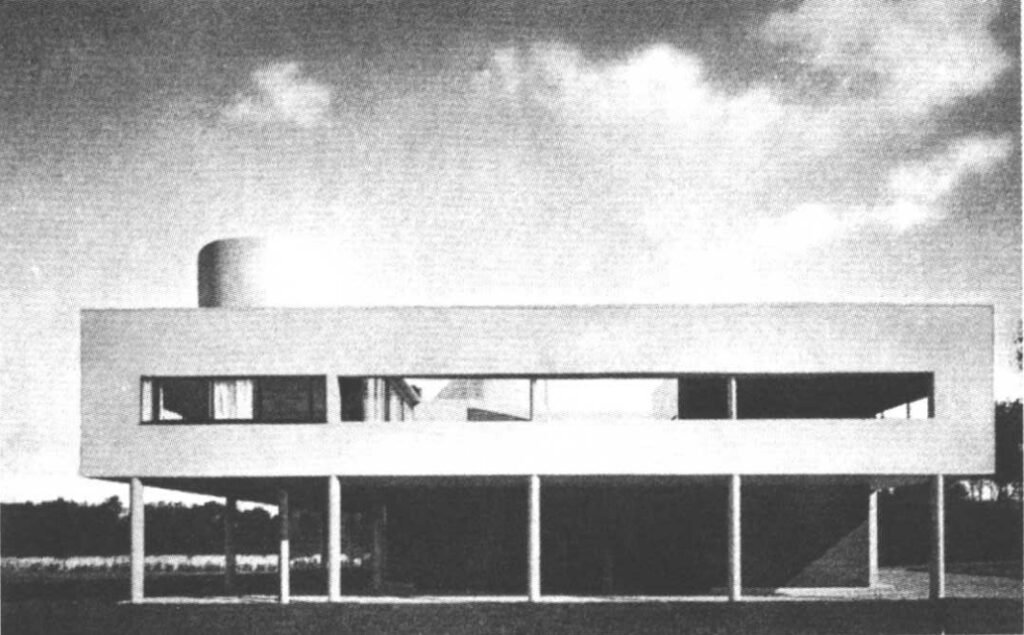

The Villa Savoye, located in the suburbs of Paris, was commissioned by clients who shared Le Corbusier’s vision of future architecture. Trusting his radical ideas, they abandoned centuries-old design traditions in favor of an entirely new framework made of reinforced concrete.

The villa features a simple square form, with most of the ground floor left open, allowing cars to drive directly into the structure. The living spaces begin on the second floor, where a significant portion is dedicated to an outdoor garden. A ramp connects the second floor to an open rooftop terrace—an unroofed space exposed to the sky for sunbathing. This unconventional building defied every classical design rule but embodied freedom and playfulness. It was a living declaration of the future of architecture. The villa’s “Five Points of Architecture” continue to guide architects to this day.

In contrast, the Ronchamp Chapel was a bold experiment in the visual potential of concrete. Here, reinforced concrete was shaped freely—thick curving walls and a massive U-shaped roof—transforming the material from a mere structural element into a tool for artistic expression. These organic, irregular forms granted Le Corbusier immense creative freedom, akin to sculpting. This free-form expression would later appear in his post-war designs, particularly in the government complex of Chandigarh, India.

Le Corbusier’s Post-War Ideals

After the war, Le Corbusier’s career entered a second phase, where he acted more as a social thinker than an architect. Faced with a world devastated by conflict, he focused on reorganizing urban life to help heal war-torn societies.

The “Radiant City” Vision

One of his most significant contributions to urban planning was the concept of the “Radiant City”. The model presented massive high-rise residential towers, efficiently addressing urban population density while occupying minimal land. Between these towers were broad highways—mostly elevated—to free up ground space for parks and recreational areas. If this layout seems familiar, it’s because modern Chinese cities have unconsciously adopted many elements from this model.

The Marseille Housing Unit: A Self-Contained Community

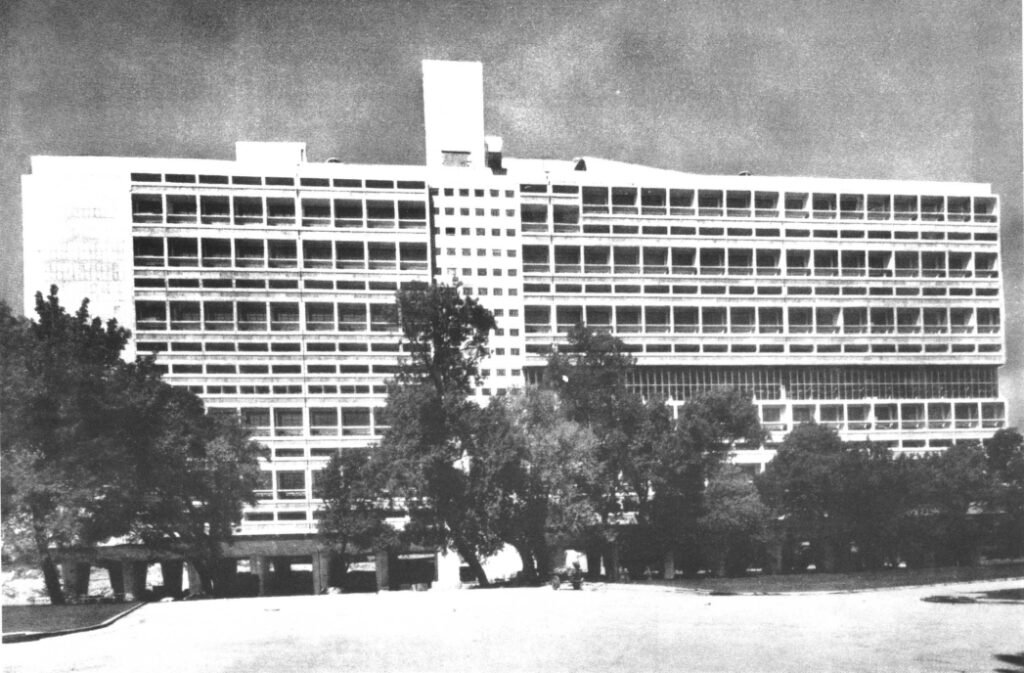

Le Corbusier also designed the Unité d’Habitation (Marseille Housing Unit) as a prototype for post-war urban housing. This structure functioned as a small city in itself, housing various public amenities.

The ground level was left open, similar to the approach in the Villa Savoye, maximizing space for public use. Inside the building, lower levels featured communal spaces such as restaurants and barber shops. The middle floors housed modular apartments with similar layouts, while the rooftop hosted additional facilities like a kindergarten. Essentially, residents could carry out all aspects of daily life without leaving the building.

Le Corbusier imagined his Radiant City filled with similar housing units, enabling cities to recover and thrive quickly after the war. While this model had many advantages—such as minimizing land use and reducing infrastructure costs—it overlooked people’s desire for personal space and a connection to nature. Over time, buildings like the Marseille Housing Unit became associated with low-cost rental housing, and the quality of life within them was often poor due to their monotonous indoor spaces.

A Utopian Dream Realized in Modern China

Though Le Corbusier’s urban utopia wasn’t widely adopted after World War II, his ideas have taken root in modern China’s rapid urbanization over the past 30 years. Today’s Chinese cities, with their towering residential blocks, expansive road systems, and high-density housing, reflect many elements of his Radiant City model.

The urban scenes we see today—of orderly roads, towering buildings, and carefully planned public spaces—are a testament to both technological advancements and the visionary work of pioneers like Le Corbusier. While his utopian dream wasn’t fully realized in the West, modern China has, perhaps unintentionally, brought many aspects of it to life.

I’m really impressed with your writing talents and also with the format on your blog. Is that this a paid subject or did you modify it your self? Anyway stay up the excellent quality writing, it’s rare to see a nice blog like this one nowadays!

Hello, I am an architect in China, and I am introducing Chinese architecture in this blog, thanks for your linking. I modify it myself.