In the sophisticated world of Chinese ancient architecture, the gable—a triangular portion of wall between the edges of intersecting roof pitches—is more than just a functional element. The Chinese gable embodies the harmony of aesthetics and tectonics, where ingenious structural logic meets cultural symbolism. Among its most fascinating secrets is the Ju Zhe technology, a refined technique in roof construction that reveals the ingenuity of traditional Chinese building methods.

In this article, we’ll explore what makes the Chinese gable unique, uncover the mechanics behind Ju Zhe technology, and explain how it fits into the broader context of Chinese wooden roof design, Dougong, and Chinese post and lintel architecture.

The Role of the Gable in Chinese Architecture

The Chinese gable, often seen in traditional buildings across the country, serves both structural and ornamental purposes. Unlike Western gables, which are usually part of load-bearing walls, Chinese gables are typically found at the ends of wooden halls and function as screens or façades.

These gables are often decorated with brick carvings, paintings, or tiles, especially in regions such as Anhui and Fujian, where ancestral halls and residential compounds feature elegantly curved and rising gable lines. Known locally as “horse-head walls” or “swallow-tail ridges,” these gables are deeply integrated into the visual identity of Chinese architecture.

Yet the most crucial role of the Chinese gable lies beneath the surface—in its subtle interaction with the wooden frame construction and roof system, especially through the application of Ju Zhe technology.

What is Ju Zhe Technology?

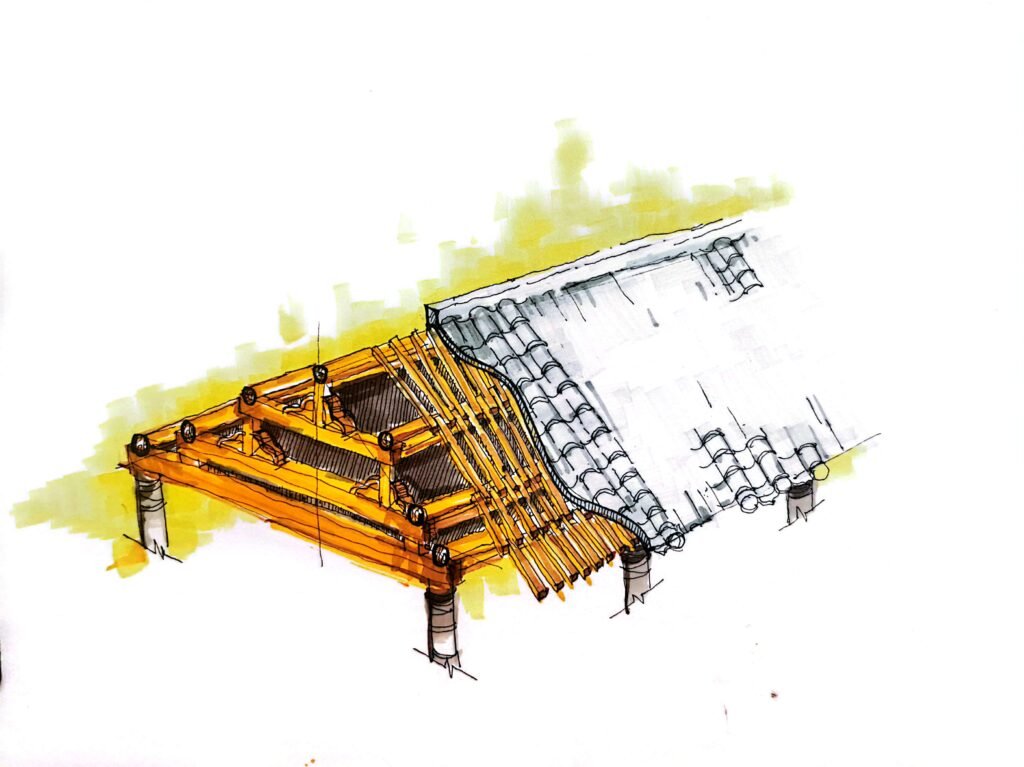

Ju Zhe (举折) is a traditional roofing technique that governs how the sloping roof of a building is lifted and folded. The phrase literally translates as “lifting and folding,” referring to the upward tilt and angular break of a Chinese wooden roof. This technique creates the elegant curvature commonly associated with Chinese roofs, especially in gable and hip or gable and single slope structures.

The tectonic essence of Ju Zhe technology lies in its geometric control. Instead of building a roof with a single angle from ridge to eave, builders used changing slopes—steeper near the ridge and flatter near the eaves. This subtle break in inclination is achieved through precise joinery and layout, enabling the roof to appear lifted and floating, while improving structural efficiency.

The use of Ju Zhe not only adds visual grace but also reduces lateral thrust on walls, a crucial consideration in Chinese post and lintel architecture, where stability relies on vertical timber posts and horizontal beams without diagonal bracing.

How Ju Zhe Interacts with Chinese Wooden Roof Structures

A Chinese wooden roof is a complex integration of beam systems, purlins, and roof tiles, supported by an underlying frame. The Ju Zhe principle is applied during the construction of the roof truss, particularly in the arrangement of rafters and purlins.

By manipulating the lengths and angles of purlins, craftsmen introduce a series of minor breaks along the roof slope. These breaks are carefully calculated to avoid abrupt transitions, achieving the fluid elegance seen in roofs of palaces, temples, and residential halls.

This method complements the broader post and lintel construction system found in traditional Chinese buildings. Since no nailed connections were used, the interlocking woodwork had to be precisely measured, and the Ju Zhe fold had to be built into the framework from the start. The gable end would then follow this articulated slope, matching the angle changes with corresponding gable outlines.

Dougong and the Gable Connection

The intricate bracket sets known as Dougong are another vital component in understanding the tectonic secret of Chinese gables. These interlocking wooden brackets not only transfer weight from the roof to the columns but also create the height and curvature necessary for Ju Zhe to take effect.

At gable ends, the Dougong sets are often minimized or simplified but still contribute to shaping the roofline. In palace architecture, such as the Wu Dian roof system (the highest-ranking roof type in Chinese tradition), the gable ends often incorporate layered Dougong tiers that align with the lifted roof profile created by Ju Zhe.

To learn more about Dougong, you can read our detailed article: Dougong – the hidden strength of Chinese architecture.

The Symbolic Dimension of the Chinese Gable

Beyond its structural function, the Chinese gable carries cultural meanings. In Confucian ideology, the gable often frames a building façade, emphasizing order, hierarchy, and dignity. The smooth fold and upward turn of the roof echo cosmic ideals of heaven and earth, which were central to Chinese architectural cosmology.

In regions where fire protection and climate considerations were key, gables were extended and reshaped to create high, flame-retardant walls. These adaptations, while local in form, still relied on the underlying Ju Zhe technology to harmonize the gable with the roof’s tectonics.

Chinese Gable vs. Western Gable: A Tectonic Perspective

While both Chinese and Western gables deal with the transition between wall and roof, their structural logics differ. Western gables typically support the roof, while Chinese gables follow the roof’s tectonic logic, acting more like architectural envelopes or visual terminations.

This difference stems from the post and lintel construction method, which doesn’t rely on walls for support. The roof, with its Ju Zhe inflections, defines the shape, and the gable is built to match. It’s this reverse relationship that makes the Chinese gable so distinct in form and meaning.

Conclusion: The Subtle Power of Chinese Gable Technology

The tectonic secret of the Chinese gable lies not in overt strength but in a quiet mastery of form, proportion, and technique. Through the clever application of Ju Zhe technology, traditional builders created roofs that were both lightweight and expressive—floating above wooden frames in elegant arcs.

Understanding the gable’s role unlocks a deeper appreciation of Chinese wooden roof systems and their unique engineering logic. From Dougong brackets to post and lintel structures, every element works together in a cohesive, time-tested tradition.

To explore more aspects of Chinese traditional roofs, visit our articles:

- What is Ying Shan roof in Chinese architecture

- Wu Dian roof – the highest ranking of Chinese roof

- What is post and lintel construction in Chinese architecture

The Chinese gable, with its graceful lines and hidden complexity, continues to inspire architects and scholars alike, offering timeless lessons in how tectonics and aesthetics can be woven into a single, unified whole.