When discussing classical architecture, the term column order immediately calls to mind the iconic forms of ancient Greece. The Greek system of columns – Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian – has long defined the visual language of Western classical architecture. Yet, many are surprised to learn that Chinese architecture developed its own principle of column order, rooted in wooden construction and reflected in the intricate system of dougong (bracket sets). In this article, we will explore how Chinese architectural theory parallels and differs from its Greek counterpart, with particular attention to the works of Liang Sicheng, the father of modern Chinese architectural studies.

The 3 Column Orders of Greek Architecture

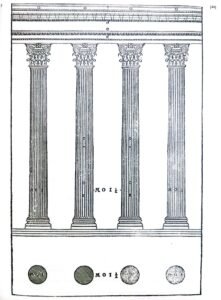

Ancient Greek architecture established three principal column types, known as orders. Each order defined not just the column itself, but also its base, capital (chapiter), proportions, and entablature.

Doric Column

The Doric column is the earliest and simplest of the three. It is sturdy, fluted, and typically lacks a base, standing directly on the stylobate. The capital consists of a rounded echinus and a plain square abacus. The Doric order projects strength and simplicity, often used for temples dedicated to powerful gods like Zeus or Athena.

Ionic Column

The Ionic column is more slender and elegant than the Doric. It features a base, a fluted shaft, and a distinctive capital with volutes (scroll-like spirals). The Ionic order conveys refinement and grace. It is often associated with temples dedicated to female deities, such as Artemis. Because of its balanced proportions and decorative richness, the Ionic column became a favorite for civic architecture.

Corinthian Column

The Corinthian column is the most ornate of the three. Its capital is decorated with acanthus leaves and volutes, creating a lush, intricate appearance. This order appeared later in Greek architecture and was adopted extensively by the Romans, who favored its decorative quality for grand public buildings.

The three orders together form a coherent system of architectural vocabulary that defined how Greeks articulated structural and decorative elements. They set a precedent for European architecture for over two millennia.

The Counterpart of Column Orders in Chinese Architecture

Chinese traditional architecture does not use stone columns like the Greeks did. Instead, it employs wooden pillars as vertical supports. Nevertheless, there is a comparable system of classification and proportion that governs their design.

Liang Sicheng’s Research on Chinese Column Orders

Liang Sicheng (1901–1972), the pioneering scholar of Chinese architecture, first proposed that Chinese architecture possesses its own form of column order. Liang systematically studied ancient architectural manuals, such as the Yingzao Fashi (Building Standards) of the Song Dynasty, to reconstruct the proportional relationships of pillars, beams, and brackets.

He compared the dougong – the interlocking wooden brackets that sit atop pillars – to the Greek capital. Just as the Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian capitals define the visual identity of their columns, the dougong system provides the transitional element between column and roof in Chinese buildings. The complexity and size of dougong varied depending on the building’s rank and function, much like how the Greeks selected Doric or Corinthian orders based on the building’s dignity and purpose.

Pillar Classification and the Cai-Fen System

In Chinese architecture, pillars are proportioned according to the cai-fen system, a modular measurement method recorded in Yingzao Fashi. This system divides the building’s design into a certain number of “fen” (modules). The diameter of a pillar might be, for example, one-tenth of the building’s bay width. Its height is then calculated as a multiple of its diameter. The type of dougong attached to the pillar depends on its rank – from simple one-step brackets for ordinary halls to multi-step complex bracket sets for imperial palaces.

Examples of pillar classifications include:

- Jian Zhu Zhu (main hall pillars): The primary load-bearing columns, typically the largest in diameter.

- Que Zhu (gate pillars): Used for palace gates or ceremonial gateways, often painted or carved.

- Yu Zhu (perimeter pillars): Smaller pillars forming verandas or corridors.

When paired with specific dougong types, the combination creates a recognizable “order.” Liang Sicheng’s contribution was to formalize this as a principle, bringing Chinese wooden construction into dialogue with Western classical theory.

The Contribution of Chinese Column Order to the Ternary Form of Chinese Architecture

One of Liang Sicheng’s most important observations was that the Chinese column order is crucial to understanding the ternary form of Chinese architecture. This ternary form consists of three major horizontal divisions: base (platform), body (pillars, walls), and roof (crowned with its own tiered structure).

Role of Columns and Dougong in Ternary Form

The pillars act as the “body,” providing vertical rhythm and setting the spatial grid. The dougong serves as the visual and structural mediator between the pillars and the roof. The size and elaboration of dougong directly influence the perception of the roof’s weight and the overall dignity of the building.

Just as the Ionic column gives a sense of lightness to a Greek temple, a building with more complex dougong appears more elevated and prestigious. This is especially evident in imperial architecture, such as the Hall of Supreme Harmony in Beijing’s Forbidden City, where massive pillars and intricate bracket sets create a majestic impression.

Architectural Hierarchy and Column Order

Column order in Chinese architecture also played a role in defining hierarchy. Official buildings, temples, and palaces had strictly regulated pillar dimensions and dougong types. This system reinforced social order, just as the selection of Doric or Corinthian orders conveyed the intended solemnity or refinement of a Greek temple.

Conclusions

The concept of column order provides a powerful framework for comparing Greek and Chinese architecture. While the Greeks developed Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian columns in stone, the Chinese evolved a system of wooden pillars and dougong that served a similar structural and symbolic role. Liang Sicheng’s research not only revealed this parallel but also elevated the study of Chinese architecture to a global academic dialogue.

Understanding the Chinese column order helps us appreciate the ternary form of traditional Chinese architecture, where every element – from the raised platform to the soaring roof – is carefully proportioned. For enthusiasts of architectural history, this comparison between the Ionic column and the Chinese pillar with dougong highlights how two great civilizations solved the same challenge: uniting structure, function, and beauty.

For further reading on related topics, see our articles on Wu Dian roof – the highest ranking of Chinese roof, What is post and lintel construction in Chinese architecture, and How a carpenter constructs the frame of traditional Chinese house.