Yingzao Fashi: the 12th-century Chinese building manual

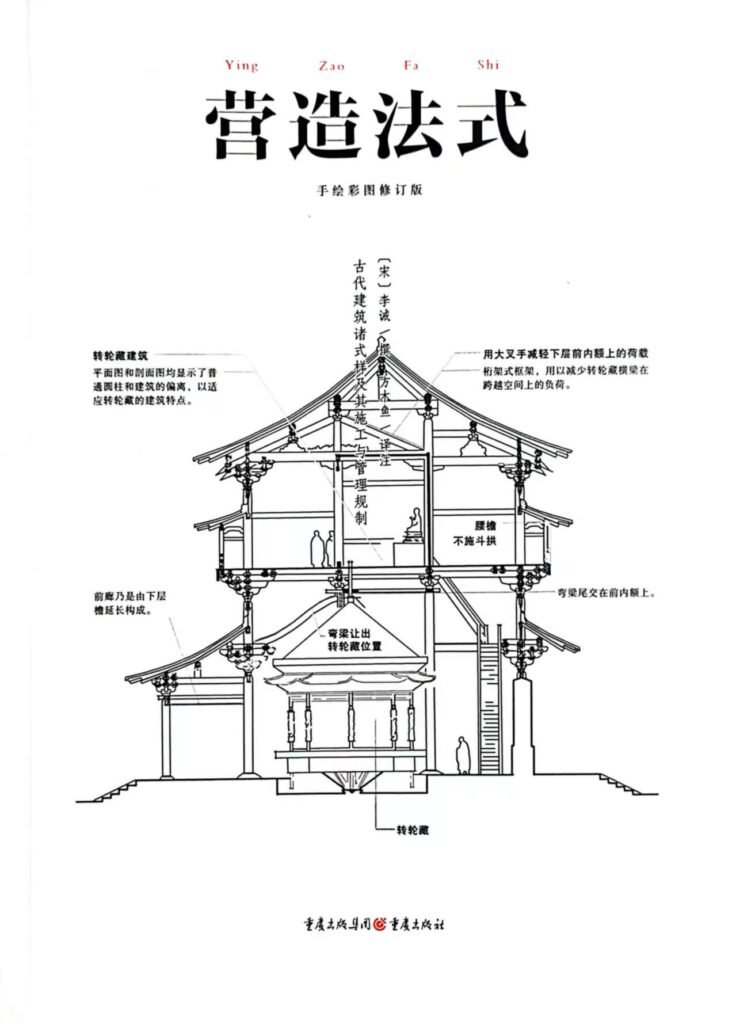

In the history of Chinese architecture, few texts have shaped building standards as profoundly as the Yingzao Fashi (營造法式), the construction manual compiled during the Northern Song dynasty in 1103. Authored by Li Jie (李誡), a court official and the Director of Buildings under Emperor Huizong, this monumental work represents the first comprehensive and officially sanctioned architectural treatise in China.

The Yingzao Fashi unified the construction principles that had developed over centuries across different regions of the empire. Before its publication, architectural techniques varied widely between provinces and workshops. Craftsmen often relied on local traditions, which made large-scale public works inconsistent. By standardizing terminology, materials, measurements, and techniques, the Yingzao Fashi created a unified language of architecture for the Song court and its craftsmen.

This manual contains thirty-four chapters that cover everything from the classification of buildings and decorative standards to painting colors, labor costs, and the use of materials. Among all its contributions, the most important is the systematization of Dougong (斗拱) — the interlocking wooden bracket set that supports Chinese roofs and eaves. The book provides the earliest fully codified system for Dougong construction, defining its size, proportion, and naming conventions in a way that could be replicated throughout the empire.

For readers exploring related architectural elements, see post and lintel construction in Chinese architecture and the Wu Dian roof – the highest ranking of Chinese roof.

The Standardization of Measurement via Dougong

The concept of “Cai” and “Qi”

At the heart of Yingzao Fashi lies a precise measurement system that connects every part of a building to a shared scale. The manual introduces two key units — Cai (材) and Qi (契) — that regulate the proportions of architectural members, particularly the Dougong.

- Cai (材) refers to the timber grade or standard material unit. It represents a modular dimension used to define the thickness and width of beams, columns, and Dougong blocks. The Song government defined eight grades of Cai, each with specific dimensions. A larger Cai grade corresponded to more prestigious structures such as palace halls or official temples, while smaller grades were applied to common buildings.

- Qi (契) refers to the ratio or degree of projection from the wall, usually associated with the overhanging parts of the Dougong set. It defines how far a bracket or beam extends outward from the wall plane. This system ensured proportional harmony between structural elements and the overall building scale.

How Dougong reflects standardization

In Yingzao Fashi, the size of each Dougong component — including the Dou (斗), a wooden block, and the Gong (拱), an arm-like bracket — is calculated as a function of the Cai. For example, a particular grade of building, using a 6th or 7th Cai, would determine the exact length and width of every bracket arm and block in the Dougong set. This approach allowed craftsmen to work from standardized tables rather than intuition.

Such precision marked a significant shift in the organization of building work during the Song dynasty. State and temple projects could now rely on consistent proportions and predictable structural performance. The Yingzao Fashi thus became not only a construction manual but also an instrument of bureaucratic control, ensuring that imperial and regional projects followed the same engineering logic.

This unified metric system also influenced later dynasties. Even in the Ming and Qing periods, carpenters referred to Cai as the core dimensional rule, maintaining a continuous architectural tradition across centuries. For further discussion on traditional timber systems, see How a carpenter constructs the frame of traditional Chinese house.

The Naming Method of Dougong in Yingzao Fashi

The structure of naming

One of the most sophisticated sections of Yingzao Fashi concerns the classification and naming of Dougong types. The Song builders developed a precise naming method based on the number of overhanging “Gong” (拱) and “Ang” (昂) — the inclined bracket arms that project outward beneath the eaves.

For instance, a Dougong labeled as “七鋪作重拱出雙抄雙下昂” can be interpreted as:

- 七鋪作 (qi pu zuo) – “seven-step bracket set,” meaning the Dougong contains seven tiers of brackets;

- 重拱 (chong gong) – “double bow bracket,” indicating a secondary layer of curved arms;

- 出雙抄 (chu shuang chao) – “double projection,” referring to two overhanging bracket arms extending outward;

- 雙下昂 (shuang xia ang) – “double lower angled arms,” denoting two inclined supporting members beneath.

This elaborate naming system reflects the high level of organization in Song architecture. Each term describes not only the visual form but also the structural logic — how loads transfer from the roof down through the interlocking wooden members to the columns below.

Classification by function and rank

The Yingzao Fashi divides Dougong into several hierarchical categories based on the building’s importance. High-ranking halls, such as palace or temple buildings, used more complex and decorative Dougong sets, while ordinary dwellings adopted simpler versions.

For example:

- High-grade Dougong (大木作) appeared in monumental halls with multiple eave layers.

- Middle-grade Dougong (中木作) served government offices or medium temples.

- Small-grade Dougong (小木作) supported less significant structures like storage pavilions.

Each classification directly corresponded to the Cai measurement system, linking the Dougong’s form with the building’s function and rank. This demonstrates how Song architects encoded social hierarchy within architectural proportion — an enduring principle visible in later dynastic styles such as Ying Shan roof structures and Chinese traditional house types.

Craftsmanship and modular precision

The Yingzao Fashi’s Dougong designs are not only technical diagrams but also aesthetic templates. They define the angle of each bracket arm, the spacing between tiers, and even the ornamental curvature of projecting members. The naming conventions allowed craftsmen from different regions to communicate using shared terminology — a key achievement in a vast empire where dialects and traditions varied.

Every Dougong type had both a structural purpose (to distribute roof loads) and an artistic one (to convey rhythm and hierarchy). The modular approach of Yingzao Fashi made it possible to replicate elegance through standardization — a principle that later influenced East Asian wooden architecture, including Japanese and Korean bracket systems.

Conclusions

The Yingzao Fashi stands as a milestone in the history of Chinese architectural theory and practice. By introducing standardized measurement units such as Cai and Qi, and codifying the construction and naming of Dougong, it transformed craftsmanship into a scientific discipline. The book turned what had once been an oral tradition into a unified national standard for design and construction.

Through this standardization, Song architecture achieved remarkable precision, efficiency, and symbolic order. Every Dougong, beam, and column followed proportions grounded in the same logic — one that balanced technical stability with aesthetic refinement. The Yingzao Fashi thus became not merely a manual for builders but a statement of imperial rationality and artistic harmony.

Today, studying Dougong through the lens of Yingzao Fashi allows us to understand the engineering intelligence behind traditional Chinese architecture. It reveals how ancient craftsmen merged geometry, modular thinking, and symbolism into enduring wooden structures — a legacy still visible in surviving Song temples and beyond.

For more explorations of traditional Chinese architectural systems, visit archinatour.com, where related topics such as mortise and tenon construction, and the art of Chinese city walls provide a broader view of the technical and aesthetic traditions that define China’s built heritage.